Jay Z’s ‘Reasonable Doubt’ Outlined His Hustler’s Ambition and Conflicted Soul

"Serve like Sampras,

Play fake rappers like a campus

Le Tigre.

Son, you're too eager

You ain't having it? good, me either

Lets get together and make this whole world believers..."

In 1996, it was hard to believe that Reasonable Doubt would be an album anyone would be celebrating two decades later. Jay Z's seminal debut arrived in June with an unceremonious thud--despite the fact that the Brooklyn rhymer had been on the underground radar for years, having appeared on tracks by Jaz O, Big Daddy Kane, Mic Geronimo, Original Flavor and Big L, but he'd been buzzing most earnestly since his 1995 single "In My Lifetime."

He followed that single with "Dead Presidents" and "Ain't No N----" in early 1996, two tracks that seemingly set the stage for what should have been an Illmatic-style instant classic. But when Reasonable Doubt was released in June 1996, Jay Z was a hip-hop afterthought.

The Death Row/Bad Boy feud was in full swing, with 2Pac's All Eyez On Me still dominating the charts. The Fugees were also at the height of their popularity; The Score had been released in February and Nas had just dropped his Lauryn Hill-assisted single "If I Ruled the World (Imagine That)" garnering him his first real taste of mainstream success. The Notorious B.I.G. was two years removed from his hit debut Ready To Die, but his singles with Junior M.A.F.I.A.--in particular, "Get Money"--were still riding high on the charts into early 1996.

It was the dawn of rap artists and albums crossing over at an unprecedented rate, and into that atmosphere dropped one Shawn Carter. Viewed by some as an also-ran to the likes of Biggie and Nas, Jay's new album wasn't a big deal to a lot of rap fans caught up in the hype of East v. West or to those more invested in the burgeoning southern hip-hop sounds of upstarts like OutKast, Goodie Mob and Eightball & MJG. The world wasn't paying attention yet, but from his very first album Jay Z announced himself as a game-changer.

Reasonable Doubt highlighted the ambitions of a young man born of struggle and raised in the crack era. That descriptor is fitting of a lot of 90s rap, but Jay wasn't fueled with the kind of rage that informed a 2Pac; nor was he wallowing in the kind of self-loathing that had defined Biggie up to that point. He was angry, for sure; and he could be fatalistic--but Jay Z wasn't hopeless. He was focused. Jay's mantra wasn't "I'm going to die young, so be it." It was more like "I'm going to rise above all of this to claim what's mine. Watch me."

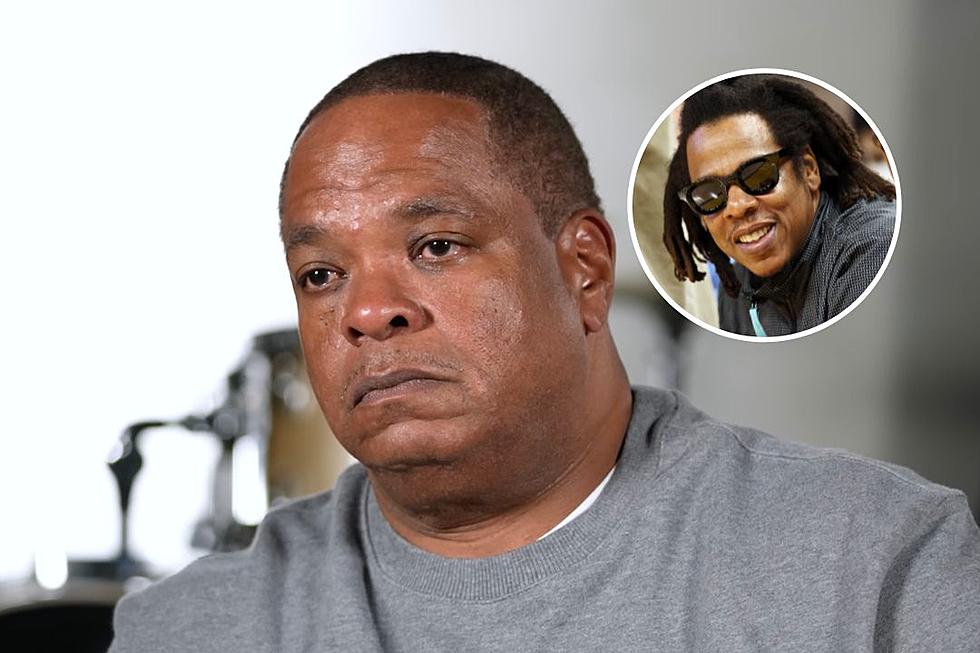

Jay had ditched Payday Records after a brief stint on the label due to Payday botching the rollout for "In My Lifetime," and he'd co-founded Roc-A-Fella Records with Dame Dash and Kareem "Biggs" Burke. They set about recording Jay's debut, and he enlisted some of the best producers in mid-90s East Coast hip-hop to handle the sounds. DJ Clark Kent, Irv Gotti, Ski (who was also working on Camp Lo's classic debut Uptown Saturday Night), DJ Premier and Knobody gave Jay a backdrop drenched in jazz and soul samples from the likes of Lonnie Liston Smith, Isaac Hayes and the Stylistics, as Jay waxed poetic about the life of a street hustler.

"At the time it never bothered me, at the bar

Gettin my thug on properly, my squad and me

Lack of respect for authority, laughin hard

Happy to be escapin poverty--however brief..."

Jay's perspective may not have been as unrelentingly dark as, say, the Notorious B.I.G.'s, but he delivered stories that were a combination of cocky and conflicted. His trademark cooler-than-thou persona was already in place and he clearly had a taste for the finer things even before he had the clout to brag about them. He was quick to dismiss "fraud willies" who were "gambling their re-up," acknowledging that he'd "rather die enormous than live dormant" on a song like "Can I Live," while breaking down the paranoia and anxiety that comes from hustling on a track like "D'Evils."

"Whoever said illegal was the easy way out couldn't understand the mechanics

And the workings of the underworld, granted

Nine to five is how to survive, I ain't trying to survive

I'm trying to live it to the limit and love it a lot..."

There was a painful pragmatism in Jay's point of view that wasn't quite as nihilistic as many of his peers. His soul was paying the price for his ambitions, but he only saw the streets as a means to an end. He saw clearly how trapped one could become in that lifestyle, and he was determined to convey that in his music while also being honest about how he'd used that lifestyle to push him to higher heights. That ambitious nature would only become more prominent as his fame and Forbes worth grew over the years, but even at this nascent juncture in his career, Jay was not going to be settling for martyrdom--he wanted to be a mogul. And he didn't apologize for that.

That hustler's ambition would be wildly influential in the coming years; as many 2000s rap stars; from the Clipse to T.I. to Dipset to Jeezy to Rick Ross would exhibit many of the same qualities extolled on Reasonable Doubt. And while Diddy had played an obvious role in "flossy rap" becoming standard, he never had Jay Z's artistic credibility. Jay's approach felt authentic--and achievable.

Reasonable Doubt famously didn't set the world on fire in 1996; but it proved to be both purposeful and prophetic. Over the next nine months, hip-hop would lose both 2Pac and Biggie, the Fugees would break up, Snoop Dogg would drop the weakest album of his career and soon after, Nas would fall into a mid-career slump that he wouldn't fully shake off until the early 2000s. That's not to say Jay's subsequent ascension to superstardom happened just because of others vacating the top spot; Jay himself didn't really get things totally "right" until 1998. Reasonable Doubt didn't sell enough for him to lay claim to alpha dog status in hip-hop and his 1997 sophomore album In My Lifetime, Vol. 1 was plagued by too many Bad Boy-esque singles that were poorly received; Jay Z doesn't really become the Jay Z that everyone recognizes until 1998s Vol. 2: Hard Knock Life, when his creativity and commercial clout finally gelled with a hit album.

No, Reasonable Doubt is prophetic because Jay Z told you back then that he was going to win. He made it plain that he was one of the most unflinchingly capitalist artists in rap, and he made it clear that he wasn't going to stop until he had New York City's throne. By the time he got there, he had much more than NYC in his pocket; he became the biggest rapper in the game. It might have taken a while, but he did give us a blueprint for his plans back in 1996.

Even if most of us didn't recognize it until five years later.

More From 107.3 KFFM