Coronavirus Is Bringing Out the Best in Pro Wrestling

It is the hoariest cliché in live entertainment: “The show must go on.” But right now, all around the world, the show cannot go on. As coronavirus sweeps the globe, public gatherings are banned, everything from Broadway to movie theaters are closed. There are no sports. There is little entertainment.

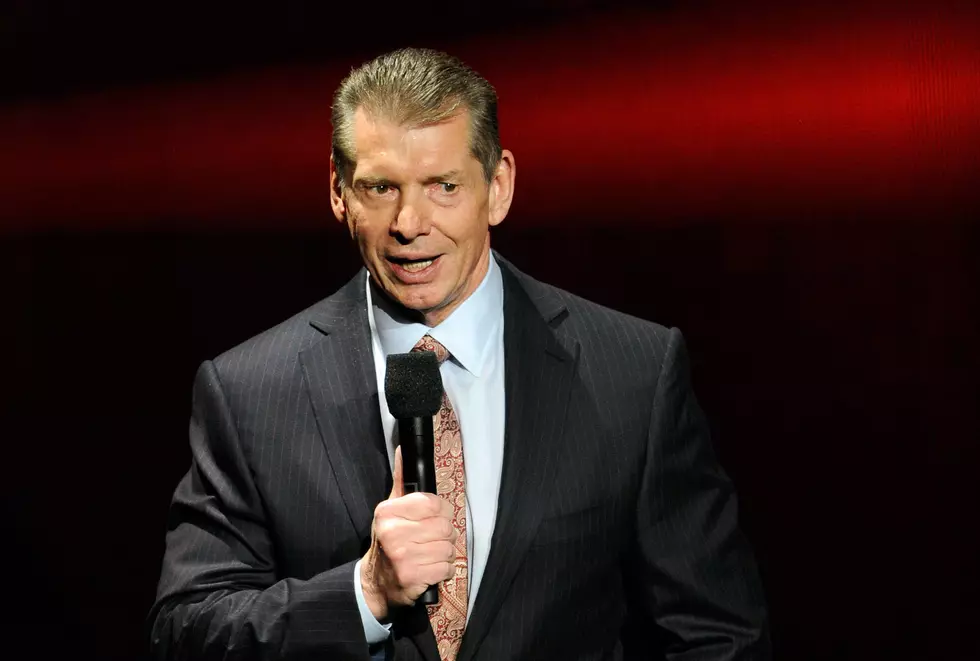

Strangely though, at least for the time being, there is “sports entertainment,” the nomenclature invented by WWE owner Vince McMahon to describe what the rest of the world calls professional wrestling. While the NBA, NHL, and Major League Baseball have already suspended play for weeks and months, both McMahon’s WWE — and their new upstart competition, All Elite Wrestling — have continued to produce new shows in empty arenas.

On a more typical week, WWE’s two flagship shows, Monday Night Raw and SmackDown, are filmed live in stadiums around the country in front of thousands of screaming and cheering fans. For now, all those stadiums are closed. Since last week, the WWE has broadcast their shows from the company’s Performance Center in Orlando, Florida, a fitness and training complex.

Usually, the WWE’s wrestling matches and “promos” — monologues from and interviews between the wrestlers — are performed in the ring and directly to large audiences of fans, who are encouraged to voice their enthusiasm or displeasure for the proceedings however they see fit. Some of the matches performed in the empty space of the Performance Center feel sluggish compared to the same sort of segment in front of 20,000 fans — but the promos might work even better this way. You may have seen several of WWE’s recent segments go viral on social media, like this one between WWE’s stalwart good-guy John Cena and Bray Wyatt, a supernatural character who goes by the nick name The Fiend:

Here’s another compelling recent example, from Monday’s Raw, where Edge — a performer who returned to competition earlier this year after being sidelined since 2011 with what appeared to be a career-ending injury — challenges a wrestler who attacked him and tried to permanently end his career a few weeks ago. If Edge had delivered this promo in front of packed arena, he probably would have spent a lot of time pacing around the ring, playing to the fans, pausing to let them respond what he was saying, and then responding to whatever they yelled at him. In an empty arena, he was able to look straight into the lens and speak, quietly but forcefully, and straight from the heart.

In addition to the “award worthy” tag, I’ve seen some compare these empty arena wrestling promos to Shakespearean drama. For most non-wrestling fans, the connection sounds laughable. The common conception of professional wrestling is that it’s fake, phony, and sleazy — an image that wasn’t exactly helped by the industry’s last heyday of popularity in the late ’90s and early ’2000s, when WWE became phenomenally popular in mainstream culture while catering to young male audiences with scantily clad female performers and raunchy jokes and commentary.

Those salacious days are long gone — and what remains has now been distilled to its essence by these empty arena shows, revealing an art form that is Shakespearean at its core. The men in the videos above are performers standing alone, on an empty stage, pouring their souls out to the camera. Where else on TV are you going to give someone give a dramatic soliloquy? What’s more Shakespearean than that? (Don’t forget, Shakespeare wrote King Lear and Macbeth under quarantine.)

Here’s another example. Last fall, Jacksonville Jaguars co-owner Tony Khan launched All Elite Wrestling on TNT as the first truly serious competition to WWE in many years. Their roster is comprised of former WWE wrestlers, independent performers, and talented young upstarts. One of the show’s main heroes — and one of AEW’s main executives — is Cody Rhodes, who opened this week’s AEW Dynamite with a passionate promo about the state of the world, the state of his company, and his desire to entertain their fans even in these very challenging times.

AEW very cleverly positioned their camera so that you couldn‘t see the empty seats in their arena, and planted wrestlers who weren’t in action around the ring to provide some replacement crowd noise. (One of the company’s top villains, the pompous Maxwell Jacob Friedman, provided some top-notch comedy as he heckled the heroes and tried to place wagers on the matches.) It wasn’t the same as a regular show, but it was closer than I anticipated, and about as good as anyone could produce under the circumstances. Watching Dynamite, you could almost convince yourself for a few moments, that the world outside wasn’t falling apart.

It’s very fair to question the decision to proceed with any matches at all in a pandemic. It seems pretty clear that people who are asymptomatic can transmit coronavirus, and even if professional wrestling is staged, it still involves a lot of physical contact. One assumes that if anyone in either AEW or WWE becomes sick with coronavirus, that would be the immediate end of their empty arena shows.

For now, though, the men and women of WWE and AEW are doing impressive work at a time when any distraction is incredibly welcome. WWE can’t hold its annual WrestleMania at Tampa’s Raymond James Stadium as planned, so they’re preparing to film it at the Performance Center — and expand the show to two straight nights on Saturday, April 4 and Sunday, April 5. A lot could happen in the next few weeks that could force them to cancel even that contingency. But for now, the show goes on.

Gallery — Binge-Watch Recommendations For All Your Favorite Streaming Services:

More From 107.3 KFFM